Randi Starrfelt, University of Copenhagen

Once we have successfully learned how to read, it continues to be easy for most of us. But for some people it can be an immense challenge. In developmental dyslexia, the process of learning to read is disrupted, while in alexia – or acquired dyslexia – brain damage can affect reading ability in previously literate adults.

Patients with pure alexia lose the ability to read fluently following injury to areas in the rear part of the left hemisphere of their brain. The curious thing is that they can still walk, talk, think, and even write like they did before their injury. They just can’t read. Not even what they have written themselves.

Some patients lose the ability to recognise letters and words completely, but more commonly, patients with pure alexia can recognise single letters and will spell their way through words to identify them. As a result, some researchers prefer the term “letter-by-letter reading” to pure alexia.

Pure alexia as a syndrome was first described more than 120 years ago, but researchers still disagree on the cause of the reading problems. They agree that a lesion in the brain causes the problems, but they can’t agree on which cognitive mechanisms may be responsible, or even how the disorder should be defined.

Not a language problem

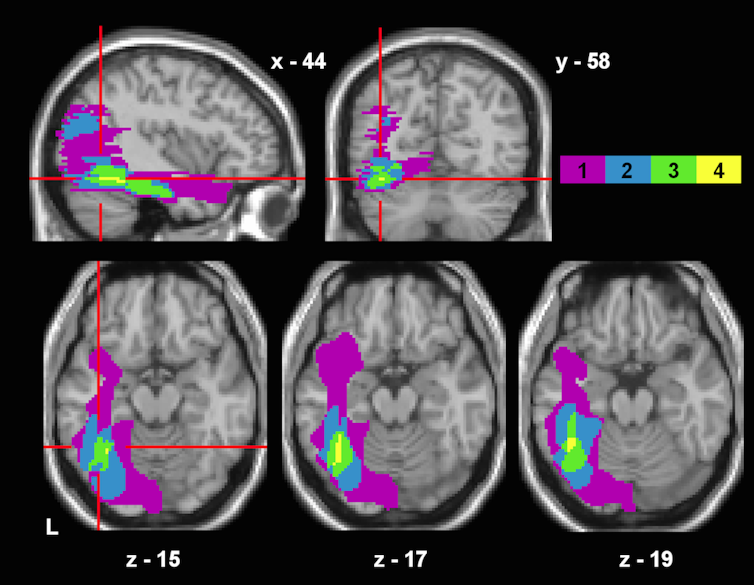

Evidence from functional brain imaging has led to the idea of a brain area that is specialised in recognising words and letters, called the “visual word form area”. It is this area that is commonly damaged in pure alexia. However, the role of this area in the way we read is highly debated and there is disagreement about whether it is reading-specific, or important for all sorts of visual recognition, such as looking at images or even faces. The same questions are discussed regarding pure alexia: whether the disorder is specific to reading or a more general deficit in somebody’s visual processing ability.

In most, if not all cases of pure alexia, other visual perceptual functions such as recognition of numbers or objects are affected, while other language functions, like speech comprehension and production – as well as writing – may be intact.

So it makes sense to look at pure alexia as a visual disorder; if it was a language problem, we would at least expect writing to also be affected, and it’s not. It is also clear, however, that the deficit in pure alexia patients primarily affects recognition of complex visual stimuli. This is because patients with this disorder may perform normally in perceiving simple patterns.

Pure alexic patients have difficulty recognising numbers as well as letters, and also show problems in perceiving more than a few letters or numbers at the same time. So it seems that patterns must be either visually complex, or need to be linked with meaning – such as words – for pure alexic patients to be impaired. On this basis, we have suggested that the core problem for pure alexic patients, is that they see “too little too late” to be able to read fluently.

As you read the words in this article, you need to perceive and integrate multiple letters at a time to access the meaning of the words and the text. Very few other visual tasks demand the same speed and span of apprehension for successful recognition, which is why patients with pure alexia rarely complain of any problems other than in reading.

When letters come easier than words

For normal readers, integrating letters into words is a very simple task that we perform automatically and effortlessly. It may actually be more difficult to focus on a single letter within a word than the word itself.

This is also known as the “word superiority effect” – that people are better at identifying words than single letters, even though words consist of letters that must be processed for the word to be recognised. This effect probably arises because of two things: first, normal readers can process letters in parallel by identifying multiple letters at a time and second, our knowledge of word meaning and word spelling helps us to identify the word.

The word superiority effect is not present in pure alexic patients: they actually perform better recognising single letters than with words. For instance, when they are asked to recognise something that is presented to them for a very short time they would recognise the letters, rather than the word itself. Perhaps it’s no wonder that many of them resort to letter-by-letter reading.

In evolutionary terms, reading is a very recent skill which takes time and instruction to learn. If a dedicated brain area is responsible for visual recognition of words then this function of the brain must have been created in each of us as we learn, rather than through evolutionary mechanisms and development.

But although the “visual word form area” may be specialised for reading, and this specialisation is created through learning to read, the area itself is not new – the brain hasn’t grown in any way. That is one of the intriguing things about the brain: even if all we learn is stored in there, the brain doesn’t grow much bigger when we learn. Instead, it seems to be reorganised, so that new skills may relocate or at least slightly displace older skills.

This has been referred to as “neuronal recycling” by the French neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene, the man who also coined the term “the visual word form area”. It seems that the visual word form area, in addition to being crucial for visual word recognition, continues to contribute to our recognition of other visual stimuli such as images of objects. Exploring this relationship between reading and other cognitive skills is a new avenue in research on reading and the brain where there is still much to learn.

Randi Starrfelt, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Copenhagen

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.